Failure and Recovery

Two school systems on what it requires to bounce back from accreditation setbacks

BY LINDA CHION KENNEY/School Administrator, August 2020

|

| A 2018 press release from Clayton County, Ga., Public Schools announcing the district’s renewed accreditation. |

Life after a school system loses accreditation is a slippery slope for school leaders who face three major groups of stakeholders in the process: the educators they lead, the communities they answer to and the students whose lives they impact.

Even for the most accomplished education leaders who are focused on continuous improvement in their schools, the stigma attached to lost or marginal accreditation is a powerful force to contend with while working to regain footing, funding and faith.

School leaders who faced these predicaments in Georgia and Missouri discussed the depth and breadth of the problem and its solutions, which in turn gets to the heart of why accreditation by outside agencies is sought after in the first place.

“Every educational institution should put its students first, and accreditation helps hold people accountable as servants of the people,” says Art McCoy, superintendent in Jennings, Mo. Adds Morcease Beasley, superintendent in Jonesboro, Ga.: “Accreditation lends credibility to your work.”

Both Jennings and Jonesboro have bounced back from the disappointment and disruption that resulted when those school districts lost their accreditation status.

Regaining Trust

More than a decade after Clayton County School District, located in the suburbs south of Atlanta, became the nation’s first in nearly 40 years to lose its accreditation, people still occasionally ask Beasley questions about the dark clouds that cast a long shadow over the 55,000-student school system and the community it serves.

For the most part, fault lies with the district’s “dysfunctional” school board, according to the accrediting agency’s report, but that did little to allay the anger and uncertainty felt by students, educators and community members alike, who struggled with, respectively, anxiety about college and financial aid applications, lost public funding and stature and another sucker-punch in the throes of the Great Recession.

Count among them Monika Wiley, who as a high school assistant principal lived in Clayton County when the pre-college division of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools issued its accreditation report in August 2008 based on interviews, site visits by evaluators and district responses to information requests. “It was tough,” says Wiley, now the school district’s director of fine arts and school choice. “There was a sense of anger, mainly because we were concerned for high school students graduating from a school system without accreditation and how that would affect them.”

Likewise, parents in the community “were very, very upset, and rightfully so, because they felt their school system had let them down,” she says. “They wanted to know immediately what we were doing to retain our accreditation. We lost a lot of students who moved out of the district or went to private schools,” which in turn reduced the district’s funding based on daily attendance.

Beasley joined Clayton County Public Schools in 2017 as its chief improvement officer four years after the district regained its accreditation. A year later, under his watch as superintendent, the state renewed the district’s accreditation.

“Even then, I was dealing with that lost accreditation quite a bit,” Beasley says. “I eventually made a statement that we will not be entertaining questions about a period more than 10 years ago that has been resolved. Ever since I made that statement, and we continue to reaffirm our position, it’s become less and less of an issue.”

Swift action in the aftermath of the 2008 report by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools included then-Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue’s executive order to ensure that all nine individuals on the school board when the accrediting body began its inquest were removed, if they had not already resigned. The investigation found Clayton County officials had not taken sufficient progress toward establishing an effective school board, including enforcing an ethics policy and removing outside influences on board decisions.

Clear Messaging

Meanwhile, Clayton County educators ensured each of the district’s 59 schools was accredited through the Georgia Accrediting Commission, an independent, century-old body promoting standards for quality K-12 instruction. Then they got to work addressing “what we needed to do to regain our [district] accreditation through AdvancED,” Wiley says.

(AdvancED, the nonprofit formed in 2006 after the Southern accrediting group merged with the Northwest Central Association Commission on Accreditation and School Improvement, is now known as Cognia following its 2019 merger with Measured Progress.)

According to Beasley, rebuilding trust after lost accreditation requires a “viable, robust communications strategy” that keeps parents informed and a community engaged. “When we ask them to give us feedback, we actually receive feedback,” he says.

His team is clear in its messaging, the superintendent adds, noting a rebranding effort that involves a new vision statement, “Creating a Culture of High Performance.”

“There was a time that if you Googled us, that’s the first thing you’d see, lost accreditation,” Beasley says. “That’s not the case anymore.”

A former high school math teacher, Beasley is a strong proponent of data-driven change that informs the continuous improvement cycle and its policies, processes and procedures. Accreditation, he explains, is “something you live, not something that happens to you. Accreditation lends credibility to your work.”

Beasley adds: “Anyone who wants to do good work for all kids should welcome the process of accreditation, if they understand it, that it’s about the quality of your instruction process. If you’re engaged in the work of continuously improving your school system, you’ll be able to share your progress and the processes you use, and that’s exactly what we did.”

|

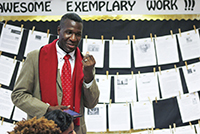

| Art McCoy, superintendent in Jennings, Mo., has raised more than $15 million in external support with a major boost from the district’s rising accreditation status. PHOTO COURTESY OF JENNINGS, MO., SCHOOL DISTRICT |

Rising Above the Brink

When Art McCoy became superintendent of Missouri’s Jennings School District, a suburb north of St. Louis, he built on the work of his predecessor, Tiffany Anderson, who over three years brought the high-poverty, high-minority district back from the brink of lost accreditation. McCoy took it a step further — accreditation in the distinction range for two years running.

Anderson, as superintendent of the 3,000-student district from 2012 to 2016,

addressed the needs and burdens of families living in poverty to allow for a deeper engagement with schools and studies and to ensure early literacy and readiness for life after high school.

With these and other initiatives, McCoy, who started his career as a math teacher at age 19, says the Jennings district functions as an “incubator for emerging ideas for career pathways and workforce development, for capital campaigns with corporate and community partners and for mental health and well-being initiatives for students and adults.”

Under his watch, Jennings, a first-ring suburb north of St. Louis, reportedly became Missouri’s first school district with more than a 90 percent minority population and more than 90 percent of its students qualifying for free lunch to perform in the accreditation with distinction range.

It’s a far cry from lost accreditation and a possible state takeover, which over the years has been all too common in St. Louis-area school districts. In 2010, for example, the state shut down the unaccredited Wellston school district, which folded into the Normandy school district, which lost accreditation two years later.

Then, in 2014, the state shut down Normandy, with the Normandy Schools Collaborative opening in its place. The collaborative in 2017 regained provisional accreditation.

“Some say losing accreditation is a stigma you never outgrow,” McCoy says. “Nobody wants that shame. But you can rise above it. It’s essential to rally together and have courageous conversations, and for leadership to defy the odds to show the real beauty and brilliance of students, which sometimes takes specific effort within the accreditation rules and regulations.”

To illustrate, Jennings school officials focused on four of the five performance standards they knew they could master: graduation rate, attendance rate, subgroup achievement and college and career readiness. The fifth standard is academic achievement, “where our overall achievement is right at the C level,” McCoy says, “so we’re working to improve on that.”

Raising Capital

The performance standards are part of the Missouri School Improvement Program, the state’s accountability system for reviewing and accrediting public school districts. Earning less than 50 percent of the system’s available 140 points leads to a state takeover. Scoring 50 to 69 percent earns provisional accreditation; 70 percent and above earns full accreditation. Scoring above 90 percent is considered accreditation in the distinction range.

According to McCoy, Jennings received 100 percent of its college and career readiness points, in part because students with block scheduling can earn eight credits more than the 24 required for graduation. That extra year of instructional time allows for student internships, apprenticeships and enrollment in college courses, made possible with community and corporate partnerships and donations.

Moreover, the STEAM College and Career Preparatory Academy offers career pathways that allow students to earn industry-related certification in a variety of fields, including construction, health services, hospitality and information technology. Likewise, students in their junior year take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery exam.

“We promise our students we’ll get them a paid internship before they leave high school or pay for every college class they take up to 60 college credits by graduation,” McCoy says.

To help fund these and other programs, including health care, housing, transportation and social-emotional and well-being initiatives, Jennings relies on outside funding sources. Over the past four years, McCoy says he has raised more than $15 million from local businesses and major corporate partners, including Emerson, Enterprise Holdings, Express Scripts/CIGNA, KPMG International, Mastercard and World Wide Technology.

“When you’re in an urban environment or an environment that is overtaxed, you can’t get blood out of a turnip, so as a superintendent you have to be resourceful and raise capital, much like a college president,” McCoy says. “For sure, hands down, accreditation helps. When the graduation rate goes up four years in a row, that’s the proof in the pudding donors want to see.”

LINDA CHION KENNEY is a freelance education writer in Tampa, Fla.