|

Skip Hults, superintendent in the northern New York state outpost of Newcomb, N.Y., stands in a school hallway that captures the international makeup of the student body.

|

Kristina Khudiakova, a high school senior from northern Russia, has a simple explanation for why she is studying 4,400 miles away in a tiny school in the middle of New York’s Adirondack Mountains: It’s her best pathway to a quality American college.

“College education in America is better than anywhere else,” she says. “There are many opportunities here and you can go anywhere you want and decide what you want.”

Khudiakova, 17, is one of seven Russian students — and 16 international students overall — attending the one-building Newcomb Central School District in 2018-19. Rather than sampling American public education the customary way for adventuresome teens, on a J-1 cultural exchange visa, they are all enrolled at Newcomb on F-1 study visas, enabling them to earn an American high school diploma and remain in this country to pursue collegiate degrees.

Pacesetting Pioneer

When it started its F-1 program back in 2007, Newcomb was a trendsetter among public school districts. Over the past decade or two, a small but growing contingent of schools have followed suit by reaching out to enroll foreign students.

A 2017 study by the Institute of International Education reported that the number of international students studying in American high schools more than tripled from 2004 to 2016, to a total of 81,981. The upward trend was fueled by students using F-1 visas.

From 2013 to 2016, the number of F-1 high school students increased by 22 percent, while J-1 exchange students decreased by 7 percent. By 2016, nearly three-quarters of America’s international high school students were studying with F-1 visas.

The number of high school students using F-1 visas is small compared to those using them for postsecondary study. Last year, more than a million college students in the U.S. carried either F-1 or M-1 visas (used for vocational study).

Moreover, the vast majority of F-1 high school students — some 95 percent — attend private schools. That’s partly because aggressive recruitment is second nature to the independent school sector. Perhaps more important, though, is the fact that F-1 students can spend only one year in a public high school, a stricture that does not apply to private schools. Even so, the Institute of International Education says that by the fall of 2016, 3,009 students with F-1 visas — mostly upperclassmen — were studying at 251 public high schools across the country.

A Slowing Trend

Christopher Page, executive director of the Council on Standards for International Educational Travel, which evaluates and certifies high school travel organizations, says various factors account for the surge in F-1s.

For international students interested in attending an American college, it’s an opportunity to become more proficient in English, adapt to American culture, earn an American diploma and increase their chances of enrolling in a quality American college or university.

For the schools, it’s a way to create or broaden diversity, widen the horizons of their students and, often crucially, bring in additional operating revenue. Unlike students on J-1 visas, F-1 students are required to pay tuition to attend public high schools.

Page notes, however, that the rapid escalation of high school F-1s is slowing as schools in China and elsewhere develop their own courses to prepare students for higher education in the U.S., and as schools in other countries attract more international students.

Page, along with officials in all four school districts interviewed for this story, also noted that under the Trump administration, more students have experienced delays and rejections in F-1 visa requests than in previous years.

Newcomb’s Win-Win

Skip Hults, superintendent in Newcomb, N.Y., says he saw two existential issues facing the remote district when he arrived there in 2006. Total pre-K-12 enrollment was just 55, and student diversity was virtually nonexistent.

“We realized we couldn’t continue this way,” he says.

His solution was to import students from abroad. It neatly addressed both issues. Newcomb’s enrollment is now 83, including the international students, and diversity has bloomed. Each day, students walk through a hallway lined with the 33 national flags from the countries of the 156 international students who have studied there since 2007. This year’s students hail from Hungary, Japan, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, Russia, Spain and Zimbabwe.

“The enrichment that the international kids provide, I can’t even express how it has impacted our school in such a positive way,” Hults says.

Newcomb senior Adrien Comeau will testify to that. Over the years, his family has hosted students from six countries, and he has learned from all of them. This year, international students will outnumber American students at graduation.

“It definitely brings a completely different environment to the school,” Comeau says.

The additional funding the students bring in doesn’t hurt. Newcomb’s international students pay $3,500 a year in tuition, along with $6,000 for support provided by their host families. Even with the low tuition, the district nets about $2,000 per student for its general fund.

Hults says he would welcome more international students if more host families could be found. In an extraordinary gesture of support this year, he and his wife, Dale, moved into a large rental house in town and are hosting 10 of the students themselves.

|

Students, parents and teachers at Liangfeng Senior Middle School, Zhangjiagang, China, learn about the opportunity to attend Craig High School in Janesville, Wis.

|

Pipeline to Maine

Hults isn’t the only school leader adding a personal touch to his international program. Frank Boynton, who is superintendent, principal, special education director, business manager and lunchroom supervisor for the 500-student Millinocket School District in central Maine, is hosting five Chinese students in his home in 2018-19.

Another seven international students live with host families in Millinocket.

Boynton says the biggest benefit is the opportunity to open up the world to his students. The arrangement also secures additional financial support for the school district, which serves a town that has struggled since the Greater Northern Paper Company, the guarantor of jobs for successive generations over a century, closed in 2008.

With tuition at $13,000 (the full unsubsidized per-capita cost of attending school in the district) and the total cost to students, including home stays and expenses, at around $25,000, the school district nets close to $150,000 per year for its general fund.

“It does allow me to keep a couple of staff that I probably wouldn’t be able to keep,” he says.

Early in 2018, the

Boston Globe carried this headline over an article about Millinocket: “A Town on the Brink of Extinction Plots a Comeback.”

Boynton, who travels to China in April and October every year to visit three partner schools and to evaluate interested students, says that after a transition period, Millinocket residents have grown used to the annual shuffling of students from abroad.

“I think initially there was some hesitation, but now they kind of look for it to happen,” the superintendent says.

Limits in Michigan

Larger school districts aren’t necessarily seeking to increase enrollment, but they are drawn to the opportunity to boost diversity in the student ranks and to give homegrown students greater international awareness — all while reaping additional, non-tax revenue. Some districts, such as Michigan’s Oxford Community Schools, have explored the limits of both community acceptance and government regulation.

The 6,200-student district, located 40 miles north of Detroit, is 96 percent white. The Oxford district receives a much lower state aid allocation than most of its neighbors. It began seeking out F-1 students in 2011, and by 2015 it was hosting 93 international students in the high school grades, most of them from China.

The district finessed the one-year limit on F-1 students by sponsoring them in their junior year, then concurrently enrolling them with nearby Rochester College, a four-year liberal arts college, in their senior year. The seniors took college courses on the high school campus, and their visas were sponsored by the college.

Meanwhile, the district had much bigger ambitions. It began negotiating a contract with Weiming Education Group in China to build a 40,000-square-foot dormitory and class-room building that would house 200 Chinese and other international students each year for 20 years. The district contended the school building, which would be off-campus and funded by Weiming, would not violate the ban on public school dormitories.

That was a bridge too far for some Oxford community residents, who vigorously opposed the plan. Jill Lemond, the school district’s director of educational solutions, says a small but voluble group was promoting “fear-based discussions.” In the end, Weiming chose not to pursue the project.

That was followed by two more blows. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security raised concerns that the concurrent enrollment plan violated the one-year limit on F-1 students. The school district now limits the students to a single year. In addition, Michigan state government has barred schools from collecting state aid for F-1 students, who were already paying tuition.

The district reassessed and is taking a new tack. This year, just one F-1 student — from India — is enrolled in Oxford. But the district has begun recruiting international students into its online Oxford Virtual Academy, which has served thousands of local students since 2009, and is growing a Virtual International Program to attract more foreign students. Oxford intends to grow back its on-campus F-1 program to between 20 and 30 students per year.

“I think what we heard from our community was that they wanted diversity in the population of students that we invited to study with us, and they wanted a number that would easily fit into our high school structure and not create a subculture of its own,” Lemond says. “We listened to that advice and have been trying to right-size our program.”

|

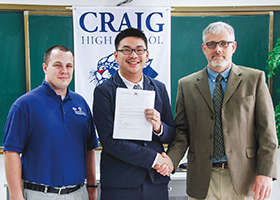

Jeff Strauss (left), an English language teacher at Craig High School in Janesville, Wis., and Karl Bryan, a counselor at the school, present an admissions letter to a high school student during their trip to Lianfeng, China, last year. The student is completing his senior year at Craig High School.

|

Diversifying Wisconsin

Students from China dominate the F-1 program because of that country’s sheer size and rapid economic growth. By 2016, Chinese students comprised 58 percent of all F-1 high school students in the U.S., according to the Institute of International Education report.

As a result, many participating districts, including the 10,300-student Janesville School District in southern Wisconsin, have direct connections to Chinese schools. All but one of Janesville’s 34 F-1 students in 2018-19 came from the same high school in Zhangjiagang in eastern China.

While that is a boon for recruitment, it comes with issues of its own. Karl Bryan, a high school counselor and Janesville’s designated official for certifying the F-1 students’ admission credentials to the federal government, says it can be more challenging for students to assimilate into the school if they arrive as a cohort of friends.

“We spend a lot of time in orientation talking about getting to know American students and making friends,” he says.

Robert Smiley, the school district’s chief information officer and head of its international program, says the district is working to diversify the program. He is building relationships in Central and South America, though it is a painstaking process.

“It takes a lot of nurturing,” Smiley says. “If it were easy, everybody would be doing it.”

Hults, the superintendent in Newcomb in upstate New York, agrees, but says that for his district, the F-1 program is well worth the effort.

“It’s bettering my school, bettering my community, bettering my kids, bettering our finances, bettering the international students’ lives,” he says. “And I believe that it’s just, in our own small way, making the world a little better, too.”

PAUL RIEDE is a freelance education writer in Syracuse, N.Y.

Additional Resources

Some organizations that can provide information on programs that host high school students on F-1 visas — and about the visas themselves.

» Council on Standards for International Educational Travel evaluates and certifies international exchange programs at high schools nationwide. It has certified 61 organizations that host students with J-1 visas and 60 that deal with F-1 visas. Its website includes a directory and a guide for high schools considering taking in international students.

» Institute of International Education focuses on postsecondary education, but researches topics that include high school programs, including the comprehensive 2017 report, “Globally Mobile Youth: Trends in International Secondary Students in the United States, 2013–2016.”

» NAFSA: Association of International Educators focuses on postsecondary education, but provides a wealth of information on immigration trends, policies and advocacy and how they affect international education and exchanges.

» U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Consulate Affairs maintains a web page, “

Foreign Students in Public Schools," offering a primer on the F-1 visa program for students wishing to attend public schools, with attention to the visa’s requirements and limitations.

» USA.gov provides links to various federal agencies on its “

How to Study in the United States” page, including

information from the Department of Homeland Security about regulations for foreign students studying in public high schools.